The Past and Present of AI Art (2/2)

A Brief History of AI Art

AI wasn’t born out of nothing in the 21st century. It grew from a number of roots.

3000 BC - the Talking Nodes of Quipu

Quipu is a method for keeping and passing information used by the Inca people in ancient times. Quipu uses nodes of different colours and materials. Sometimes there can be hundreds of nodes that were tied in different ways and at different heights to express differences in meaning. Quipu can not only record date, number and account balance but also serve as the medium for abstract thoughts and record the folklore and poetry of local cultures.

Without resorting to an alphabetic writing system, Quipu can record large amounts of information with decent accuracy and flexibility. When nodes of different colours are added to make even more combinations possible, the potential is limitless.

1842 - Poetical Science

Analytical engines can execute mathematical calculation orders on punctured cards. In 1836, a portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard, inventor of the first weaving machine, was woven using 24,000 punctured cards. In a sense, this portrait is the world’s first digital image.

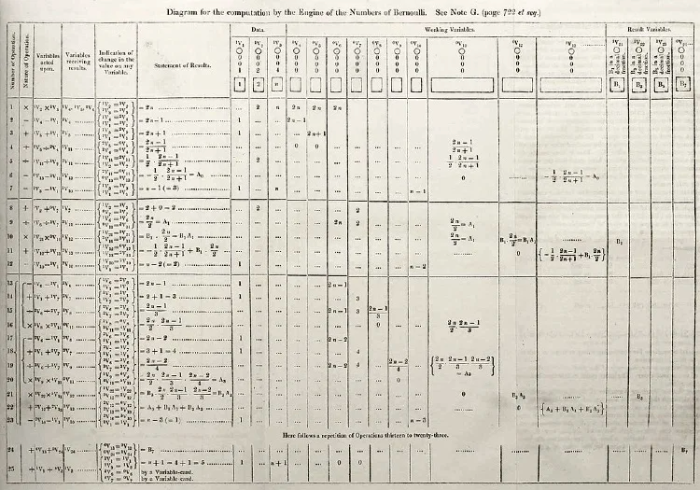

In 1842, Ada Lovelace wrote the first computer program in history. Her friend Charles Babbage designed the very first system of algorithms for his analytical engine inventions.

The first published computer algorithms are Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine Sketches (1842).

The way analytical engines weave algebraic patterns is just like how a weaving machine weaves flowers and leaves. Ada called this poetical science. Imagine if a computer can do more than computing. Can computers be used to make art? At a time when art and science are in two totally separate camps, her goal was to integrate the accuracy of science and the flexibility of art.

The basis of this belief is that our world is built upon mathematical laws. Here is an example:

Rose curve formula: ρ=a*sin(nθ), a being a fixed length, n being an integer. We can use this formula to draw a rose.

Mathematics holds the key to a lot of visually pleasing shapes and patterns. Since AI is based on mathematics, the beauty it can create is limitless.

1929 - A Machine That Could See

In 1929, Austrian engineer Gustav Tauschek invented the photoelectric reading machine.

This contraption has letter/number-shaped holes on a wheel. When light reflecting off a letter or number passes through a lens and hits the wheel, the wheel will receive the most amount of light if the shape of the letter/number matches that of the hole. When this happens, the photosensitive module on the wheel will send a signal, and the reading machine will register the correct letter or number.

The photoelectric machine is human beings’ first attempt at giving machines the power to recognize things. The method it adopted is called “template matching”, which is also the first practical recognition method.

What does it mean for humans to see through the eyes of a machine? And what does the machine actually see?

1950 - The Imitation Game

In 1943, the concept of an AI neural network was first raised. Combining algorithms and mathematics, it uses “threshold logic” to simulate the thought process of human beings. The gate to AI was thus pushed open.

Alan Turing developed the Turing test, also called the imitation game. This is a benchmark test used to show that machines can conduct intelligent behaviour indistinguishable from humans. Can machines think? Under the influence of Turing, many artists began designing similar “games” during this period of time.

Jean Tinguely used one piano, two electric power engines, one balloon and over 20 bicycle wheels to make a chaotic structure. This contraption is capable of a series of unpredictable actions that will eventually lead to its own destruction.

1953 - Reactive Machines

Gordon Pask was one of the early pioneers of cybernetics. As a psychologist and educator, his research involved bio-computing, AI, cognitive science, logic, linguistics, psychology and artificial life. He incorporated information from various media sources into his cybernetic theories and expanded the scope of the study.

In a famous exhibition: Surprising Discoveries of Cybernetics, Gordon Pask displayed a work titled The Colloquy of Mobiles. This is a type of reactive machinery capable of emitting lights in response to sounds made by human performers.

In 2020, a duplicate of Gordon Pask’s 1968 The Colloquy of Mobiles was displayed at Center Pompidou Gallery.

1968 - Cybernetic Serendipity

In the 1960s, under the influence of cybernetic art, many artists started creating “artificial life” artworks drawing their inspiration from animal behaviour, or viewing the system itself as art.

The exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity was held in the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1968. In the exhibition, Jean Tinguely displayed two of his drawing machines. These are dynamic sculptures. Visitors can choose a pen of any colour or length and at any location, and the machines can create a brand new piece of abstract art with it.

1973 - An Autonomous Picture Machine

More artists began to try using machines to create art. Some of their ideas still influence present-day art.

Picture: Untitled 1972, an early example of computer art, made by the first code-based drawing program developed by Vera Molnar

In 1973, Harold Gohen developed an algorithm named AARON, which allowed machines to draw irregular drawings like the human hand. Although AARON is only limited to a certain drawing style coded by Cohen, the fact that it can create a limitless number of works in this style makes its works the first-generation computer art.

The Age of Deep Learning

By the late 20th century, thanks to the popularization of personal computers, this industry began its fast development. More and more artists started using software programs. Into the 21st century, the availability of free learning materials for programming in combination with open-source projects on Github helped the industry grow.

In addition, researchers are building and publishing large databases, such as ImageNet, which can be used for training algorithms in categorizing and recognizing images. AI visual programs such as DeepDream are easily available to artists and the general public so that everyone can experiment with how well computers can understand different forms of visual expressions.

With all these innovations, AI art to this day has gone through three stages:

- Chatting bots

- Generative art

- Beyond generative art

Chatting bots

1995 - A.L.I.C.E

Released in 1995, Richard Wallace’s famous chatting bot A.L.I.C.E was able to learn how to speak from a corpus of natural human language gathered from the Internet.

2001 - Agent Ruby

Lynn Hershman Leeson created Agent Ruby.

2020 - Expanded Art

Since then, many more artists have created chatting bots. Martine Rothblatt modelled his bot Bina48 after his wife’s personality. Martine Syms developed an interactive chatting bot to be her digital avatar. The bot is named Mythicbeing and was designed to be a black, upward, violent, solipsistic, anti-social and gender neutral woman.

Generative Art

Artists can collaborate with AI in various ways, using neural networks and machine learning to create artworks. Examples of this include Neural Style Transfer, Pix2Pix, CycleGAN and Deep Dream. So far generative adversarial network is the technology most relevant to AI art.

2014 - Generative Adversarial Network

Generative adversarial network is a term coined by Ian Goodfellow in a 2014 thesis. He believes that GAN will be the next step for neural network, as the technology can be used to create visual effects that were possible before.

2017 - GANism was born

Around 2017, artists began testing this technology.

2018 - A Milestone of Auctioning

The most well-known example of GAN-generated art is a portrait by Obvious which sold for 432,000 at Christie’s in 2018.

Two types of algorithms are used here to create these high-resolution artworks: GAN and super-resolution algorithms. More interestingly, the authors have used arithmetic functions to sign their works.

Beyond Generative Art

In recent years, more and more artists see the purpose of AI as not merely to create images, but also to put an end to the innate prejudice people hold against AI. How this movement is carried forward will have long-lasting influences on social justice, equality, tolerance and many other important issues.